Competition within academia has led the humanities to apply scientific rationality to aesthetic experience. In The New Yorker, Nathan Heller analyses the present state of academia “in a quantitative society for which optimization…has become a self-evident good.”1 State policy and private sponsorship have favoured STEM since the end of the Cold War. The CIA and its predecessor organizations have long been involved in funding art and cultural discourse. However, investment in culture through the Congress for Cultural Freedom has generally declined since the heyday of the 60s. According to The New Yorker, enrollment in humanities programs has similarly been in decline since the end of the Cold War. Meanwhile, STEM departments across the United States receive lavish endowments. Scientific research, even at its most abstract, is associated with instrumental application and technology development. Technology can be used to increase profits, either by reducing labour and economizing on production—or through the design of commodities. Theoretical tendencies within the cultural discourses of the 20th century have also had an impact on the quantification of the humanities. Structuralist and post-structuralist thought promote a disenchanted form of study, where art is seen as something like a node in a tissue of connections (Barthes); or a product of an ideological state apparatus (Althusser). By contrast, Nabokov “famously” taught the novel by paying attention to “form, references, style, and special marks of authorial genius…an intensification of the way the reader on the subway experiences the book.”2

The quantitative form of reasoning associated with science, and the qualitative assessment of sensation (aesthetics), is a topic treated by Hegel in the terms of “faith” and “Enlightenment.”3 STEM and the humanities, quantity and quality, faith and Enlightenment are all different ways of naming two opposed tendencies brought to loggerheads within consciousness. The uncanny emerges from out of the gap of their irresolution, an incomplete understanding of the world. The uncanny is what’s at stake in the quarrel over the question: how are we to be at home in the world, given the unknown? Modernity, the institution of liberal democracy, and capitalism all represent a false stasis in the conflict; they are each a structure built on a contradiction. The truth is haunted, a defensive mechanism whose very necessity confirms the presence of a ghost.

Modernity marks the transition from the regime of the architect to the regime of the engineer, as Benjamin wrote.4 Photography, the automatic production of reproducible images, the annihilation of auratic privilege, is the second great stride from analogue to digital after the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg circa 1450.5 The magic lantern show is a proto-form of cinematography, but one which is still tied to the performance-based ontological mode of the artwork. From its inception, the cultural form that would become the form of mass media par excellence in the 20th century has been a joint endeavour of art and science. And since becoming all the rage in the 19th century, the first genre in this “pre-history of cinematography,” the pre-history of art produced for the proletariat, has been horror.6

Journalist Armand Poultier narrates an account of one of Robertson’s performances in 1798:

A young fop asked to see the apparition of a woman he had tenderly loved, and showed her portrait in miniature to the phantasmagorian, who threw on the brazier some sparrow feathers, a few grains of phosphorous and a dozen butterflies. Soon a woman became visible, with breast uncovered and floating hair, gazing upon her young friend with a sad and melancholy smile.

A grave man, seated next to me, cried out, raising his hand to his brow: ’Heavens! I think that’s my wife"; and ran off, not believing it a phantom anymore. — Castle, 35

The “uncanny illusionism” of Robertson’s magic lantern device—combined with his theatrics—was powerful enough to frighten audience members into believing a painted image projected through smoke and mirrors was “not a phantom anymore,” but instead something real. This is a Romantic reaction, which “wished to reform scientific thought by returning it to its roots in the correspondences and metaphors that make up [a] magical system….”7 His perception of the conjured woman is publicly verified, and therefore must be objective; yet it is still a resident of the spirit realm and is therefore terrifying. Romanticism wants to resolve the divide between the world of faith and the world of Enlightenment by merging nature and mysticism. New media forms, which come about through technological innovation set off a process of “scientific demystification,”8 which the past two centuries of development tells us merely displaces the fear of unhomeliness at the heart of the faith/Enlightenment divide. Robertson developed his phantasmagoria during the French revolution, a widespread secularization of society that forced the transition into the modern era through drastic means.9 In this case, the engineer, or crafter of mass media, takes over from the priest rather than the architect.

The modern era signals the death of God, and science is what the Enlightenment proposes in his place. Secularization is the perspective on education that originates from the standpoint of the faithful. Both perspectives bely where one’s allegiance lies. New media represents not only the production of cultural commodities for the proletariat, but the industrial manufacture of the means of cultural production. This is the first condition of possibility for a proletarian culture. When cameras began to be mass produced around the late 19th century, a world opened up that none of the plastic arts had given access to. Realistic images could be produced by any proletariat able to save enough money to buy a camera. Unlike painting or sculpture, the camera could be operated through a very minimal degree of manual intervention. Point and click and you have a frozen moment of time as you represented it. To produce paintings or sculptures with a comparable degree of verisimilitude requires years of training, in addition to the social position required to pursue apprenticeship and patronage. Visual media was placed in the hands of the people.

If you saw a ghost today, how would you explain it? As a hallucination caused by some chemical substance, altering the brain chemistry in such a way as to produce perceptual effects; or as a hallucination caused by a psychological disturbance; or as a physical image, the projection of light by some hidden magic lantern. All of these explanations are more likely to be offered by any post-Enlightenment subject, before they would be given to believe in something supernatural—something unknowable and alien outside of the self. Romanticism is as relevant as it ever was: no matter how much we purport to reason scientifically, there is always an emergent phenomenon that we could posit as originating out of an alien substance—the spirit realm; magic. From its earliest days, mass media has proliferated around uncanny genres. Mass consciousness does not yet feel at home in the world, and seeks catharsis in narrative resolutions of uncanny sensations. Technology mediates the cultural expression of and for the masses; what, specifically, its function is in the complex relationship between Enlightenment, faith, and modernity, is not resolved yet.

Psychoanalysis applies Enlightened rationality to the internal effects of the faith/Enlightenment contradiction. It as an attempt to categorize how unhomeliness is experienced by the individual. Social relations like capitalism are the external influences that determine the general set of signs of the uncanny. The vampire, the zombie, and the ghost are all recurrent symbols from 18th century literature through to the present. Psychoanalysis is the inward-looking, Enlightened attitude that theorizes subjectivity as a thin surface on top of something alien and unknowable within us. The unknowable becomes present to us through repressed desires, Oedipal complexes, transference, dreams, death drives: all the phenomena of mental life whose source is unknown, yet felt.

The uncanny is felt when something disturbs an “atmosphere…of involuntary repetition.”10 Life for the proletariat grinds on from one day to the next, regimented by the micro-politics of the liberal state and digital life. Modern life is structured around the basic, repetitive obligation of work and, depending on one’s fortune, the familiar comforts of home and family. A house is made of layers of bricks and mortar; a home is made of layers of repetitious labour spent keeping the walls clean. Our familiar orbits become homely when we can fade them into the background. The city, chaotic and various as it is, is still made up of patterned traffic flows; it is still layered with memories and associations imbued in the immutable element of location. The safe atmosphere created by repetition is enough to trick consciousness into forgetting that there is something alien pushing up against the borders of our entire social reality. The concrete city seems eternal in its scale and the hardness of concrete, but the loss of familiarity when a long-standing landmark is utterly changed reminds us that stability does not last. The uncanny threatens us with the knowledge that our borders are arbitrary. No matter how lovingly we labour to keep our home clean, it is as thin a protection against the unknowable as the wall of a tent against the dark forest.

The uncanny will always re-emerge in culture, recycling the same icons until consciousness is able to complete the negation of otherness and create something new out of faith and Enlightenment rationality. If we accept Marx’s materialist inversion of Hegel’s idealist theory, the prior cause of the present contradiction is the configuration of social relations. The contradiction between faith and Enlightenment at the heart of modern consciousness is a consequence of how social relations have evolved over history; as such, its resolution will appear as the resolution of the contradictions in social relationships. Scientific endeavour, empirical investigation, comes before new knowledge. The object comes into view by moving closer to it. Marxism is scientific, an offshoot of Enlightenment reasoning: but it is absolutely pragmatic in its political–economic object of investigation. The negation of otherness, the recognition of difference, becoming at home in the world, living in social and ecological harmony, the future of the humanities—what the human is—are all implicated in the project of overcoming capitalism.

For critic John Clute, horror narrative begins with a “sighting,” the initial moment when one perceives something askew in the background of the familiar. The “thickening” is the exposition, and takes up the bulk of the narrative. Thickening is the movement of the alien unknown from out of the background into the acknowledged foreground. This is followed by revelation, the culminating moment when one is forced to acknowledge that one’s home has always been utterly vulnerable; and aftermath, wherein we get a view of the ruined home.11 This is not entirely dissimilar from the basic, cross-genre structure of the hero’s journey, just phrased in terms of unsettlement. Horror narrative forces the protagonist into a confrontation with the contradictions at the heart of consciousness. The genre has been with us since the beginning of mass media, in Gothic novels; the phantasmagoria; spirit photography; early silent films like The House of the Devil (Georges Méliès, 1896); German expressionism in the 20s; Universal Horror in the 30s—right through to its contemporary popularity. Mass media trends are an index of market demand, which by no means tells us what the proletariat desires. It does tell us, however, that horror expresses something with mass cathartic appeal. Everyone in a society has the same basic cultural framework, vulnerable to the same tropes. Fear of the alien unknown is common to consciousness at this stage in history because we have all reached the same impasse.

“Ours is an age of onrushing turbo-capitalism, wherein the present feels more abbreviated than it used to.”12 Such a pell-mell tempo is precisely the opposite opposite required for the delayed gratification of the institutional change necessary to account for climate change. Looming apocalypse is the grounding sensation of the Contemporary, another contradiction that denies the future in favour of the present. Climate change is still perceived of as the presence of non-presence, a future burden that weighs on the present. Who wins the argument over whether or not the evidence of climate change is true or false is not the most immediate question. Pitting faith against Enlightenment and driving both sides to despair is not an effective strategy for dealing with present contradictions. The proletariat is not going to resolve its material conditions by dividing itself into two, fighting to death, and leaving the winner to oppose the ruling class alone. No matter our stance towards climate change, we are both not at home in the world. In order to become comfortable, consciousness must completely overcome the need to construct borders between itself and the world. To that end, anti-humanism proposes an ecological totality.

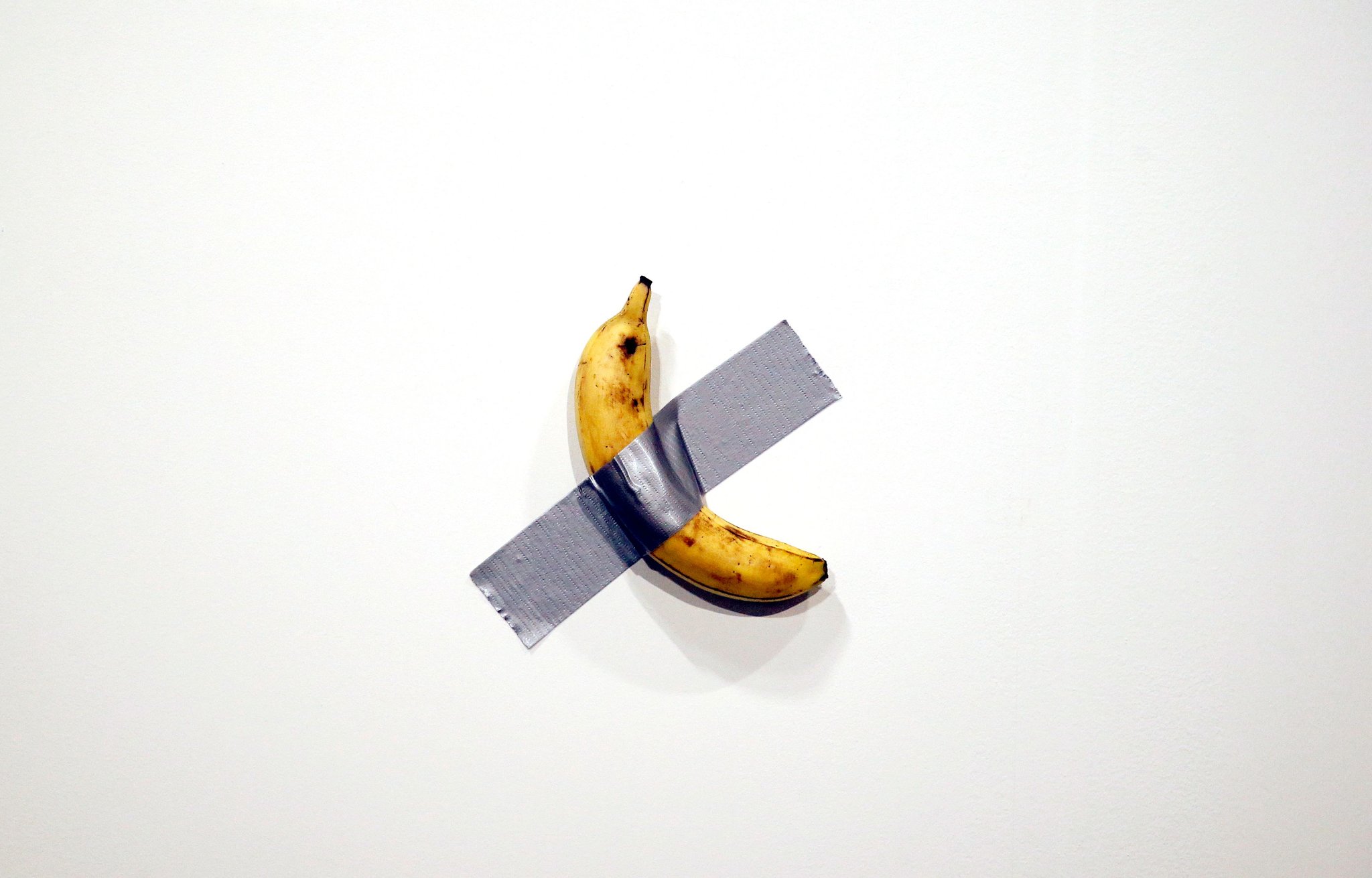

The Contemporary is a new stage in the history of modernity. It is characterized by a latent anxiety and subsequent denial of our status in relation to the ecology. Horror is still the favourite genre in the 21st century because we are still fascinated by what lies beneath the layers of contradiction that make up consciousness. Contemporary art in the legacy of Duchamp often practises a form of institutional critique that similarly exposes the uncanniness found on the outside of the borders of the artworld.13 A snow shovel purchased at the store down the street. Artisanal screenprints of the logos on mass-produced commodities. A banana taped to the wall. The kitsch associated with NFTs, created as explicit stores of financial value. All of these phenomena bring us into confrontation with the illusory substance of the border separating art from non-art. Comedian and the sale of Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days for $USD 69m takes ironic cynicism to the point of moral degradation. Postmodern aesthetics is a game played with a hand grenade: on the one hand, often unconscionable; on the other hand, as true a representation there could be of the contradictory nature of modern subjectivity.

The outcome of scientific inquiry is an object that vanishes as soon as one comes to an understanding of it, compelling more research. The Contemporary can hardly be blamed for its inability to move beyond the present instant, since science is its role model. Mass media opened up a new world for proletariat culture; whether the proletariat needs technology to develop the class consciousness necessary to overcome the ruling class is a moot question. Socialism comes out of capitalism, out of the technologically-mediated world as it has been made. It does not happen in a post-apocalyptic landscape when the slate is wiped clean. Perhaps a more pertinent question would be what the political strategy for engagement with mass media should be. How do we create a culture of critical distanciation from media, when to a large extent our entire sense of being at home in the world comes from media? What can culture contribute to a political process, and how can we do so in the interests of the proletariat?

The typical gesture that navigates digital life is a dismissive flick, scrolling the viewport from one piece of media to the next. Text and image become one homogeneous material. The old is folded into the new. The digital platforms that mediate sociality encourage the constant vanishing of the present into the future, a disassociation from lived contradictions in favour of a highly-mediated virtual world. The instrument of mass media that once opened up a world for the proletariat is turned against it, instrumentalized as perhaps the most powerful weapon yet of the enemy, since it preys on a basic universal vulnerability to the fear of unhomeliness. The question of whether or not to condone digital life and imbibing mass media is by no means a moot one, as quantitative critical theories teach us.

Amidst the depth of our present “scientific education” via new media forms—despite an official separation of church in state in the leading liberal democratic nations—a spectre haunts consciousness: the spectre of communism. The basic conflict between Enlightenment and faith persists. Two opposed modes of reasoning, each with their own claims to valid rationality.

What are we to make of anti-humanist ecological tendencies in contemporary philosophy? Why the call for “non-representational theories,” for affect theories, for what Glissant called a poetics of relation. Why the turn to atmosphere and anti-humanism? What motivates literary trends marrying aesthetic and rhetorical modes of writing? Non-representational theory is not merely a stylistics, but rather posits a new object. An inseparable ecological totality, an unfolding process of which each unique one is a part. In order to address this new object, the theoretician should endeavour to reproduce the atmosphere by reproducing the entire ecosystem. This is opposed to the typical critical operation of separating things out from each other. But how and to what extent can writing produce an entire world? Is this merely an attempt to find a new form of persuasion? Does ecology resolve the disagreement between faith and Enlightenment? If it does, what form does the movement to something new take? If it is typical political theory, what new is being offered?

Nathan Heller “The End of the English Major,” The New Yorker, February 27, 2023, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/03/06/the-end-of-the-english-major.↩︎

Heller↩︎

G. W. F. Hegel Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A. V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).↩︎

Walter Benjamin “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Selected Writings, by Walter Benjamin, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Howard Eiland, vol. 3 (1935; repr., Harvard University Press, 2006), 32–49.↩︎

Philip B. Meggs and Alston W. Purvis Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, 5th ed. (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2012)., 72↩︎

Terry Castle “Phantasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie,” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 1 (1988): 26–61., 40↩︎

Tom Gunning “To Scan a Ghost: The Ontology of Mediated Vision,” Grey Room 26 (2007): 94–127., 101↩︎

Castle “Phantasmagoria.”, 30↩︎

Gunning “To Scan a Ghost.”, 109↩︎

Sigmund Freud “The Uncanny,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: 1917–1919, vol. XVII (1919; repr., London: Vintage, 1999), 1–21., 11↩︎

Sarah Dillon “The Horror of the Anthropocene,” C21 Literature: Journal of 21st Century Writings 6, no. 1, 2 (2018): 1–25., 14–17↩︎

Rob Nixon “Introduction,” in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011)., 8↩︎

This is why “outsider art” like Daniel Johnston can sometimes appear uncanny.↩︎