When John Anderton goes on the lam in Minority Report, he employs a black-market surgeon to replace his eyes.1 Spielberg, part of the “Greatest Generation,” can only imagine a cyberpunk Panopticon in moralistic social terms, rather than as a technological reality. Omnipresent facial scans are present in certain societies,2 but they are a similar anachronism as the payphones in Neuromancer. It’s close, but misses the mark. In Foucault’s terms, “power” is economizing; it is easier to simply subjectivate people into voluntary reporting their activity through myriad smartphone apps, than to impose them to a matrix of external scanning devices.3 The contemporary subject participates in their own surveillance.4 The concept of a cyber punk is just as anachronistic: the technological regime is a product of the liberal order, and conceals its dystopian nature.

It’s these same corporate overlords that have trained the Contemporary subject to hope for nothing greater than the numbing ether of skepticism. The Contemporary has regressed to an even lower stage of Spirit than skepticism: the mass tendency is towards stoicism, of all things, which has no greater value than smooth-brained ataraxia. Technical optimization smoothes the friction of our anxious existence.

Yes, but really the conglomerates are just character-masks for the inevitable logic of capital. Digital culture and all its social potential has been confined to a protocol strictly determined by the profit motive. Tech conglomerates and hardware manufacturers have more power than states, but without the hindrance of historical precedent. Spirit has regressed to a stage prior to where it has even learned to be Unhappy—we have become slaves, stoics, to our utter debasement.

But hasn’t life always been mediated by technology? The historical record is a trace of society’s evolving relationship to technology. How do we evaluate our present addiction to smoothness without falling into the trap of thinking that the past was somehow better? Would we be better off if technology had stopped developing in 1910, or 1998, or are we on a natural path to cyborg transhumanism? The fact of technology does not mean that all technologies are good.

Writing History

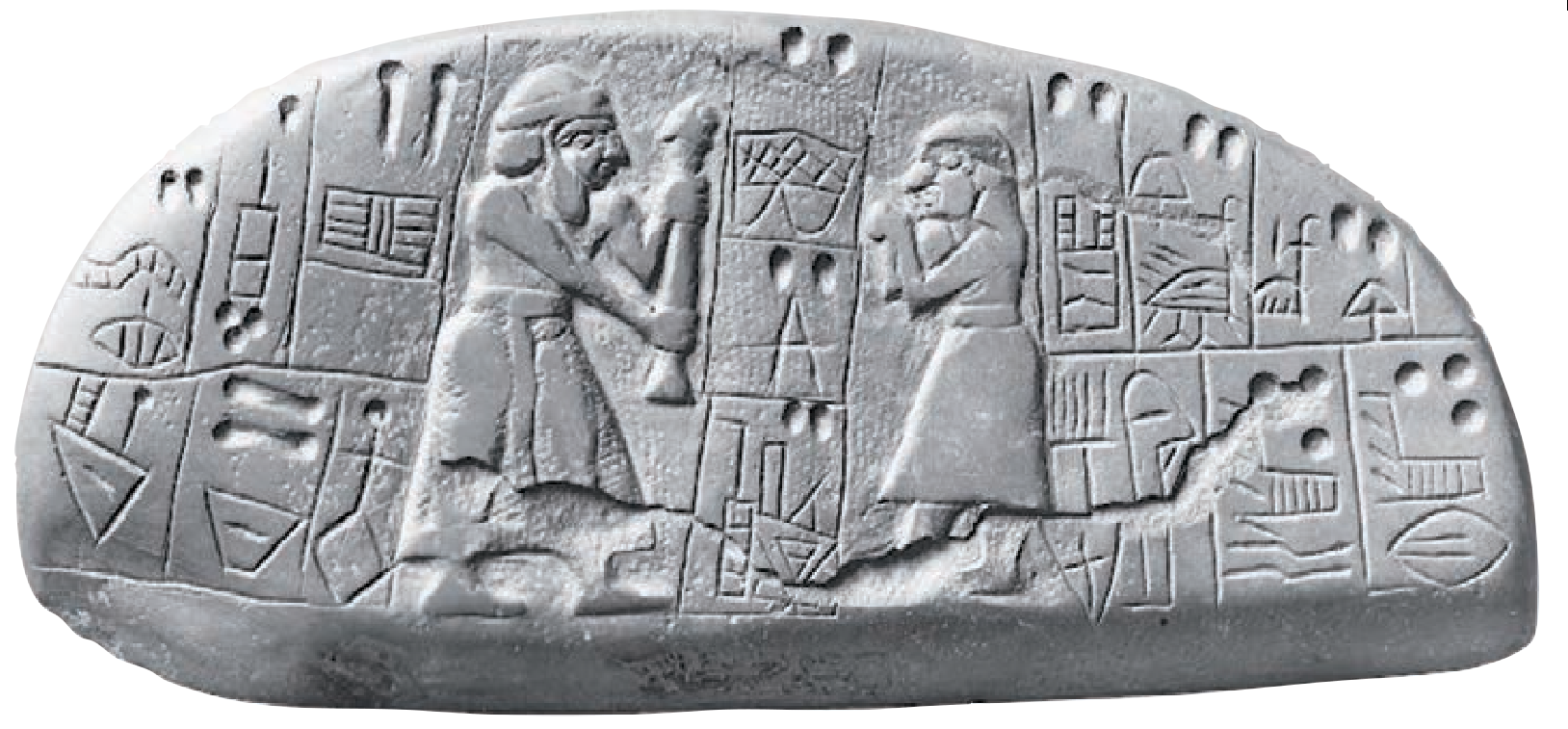

Graphic design is part of the history of the written word. When the first obelisks were unveiled in ancient Mesopotamia, their surfaces covered with the bird-like scratches of cuneiform, image and word were arranged to co-constitutive elements of the message.

Up until the height of the European medieval manuscript, graphic design developed as an aspect of the fine arts tradition. The most technically-advanced manuscript on record, the “Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry,” resembles the Gothic art of its time. However, it becomes an element of mass culture earlier than other visual media, following from the printing press, the first technology of automatic reproduction. The technique and visual culture associated with a specifically mass form of media could then begin to detach from the artisanal culture of the fine arts.5

The Voice of a Website

This website is a constant work(-in-progress). Its first function is to index and archive all my published works, both on this website and elsewhere. It is also the repository for my Diaries. However, the content that specifically belongs to this website is the research, which I am continuously developing into one big version-controlled, cross-referenced, linked and tagged, cited, media-rich Gesamtkunstwerk. A combination of design, information architecture, knowledge management and production. Drafts, fragments, notes, revisions, photographs, visual material: a collection of rags.6

There is, however, a significant inconsistency with the website’s voice. The research is written in a standard address, without literary depth. The Diaries have depth (whether or not they have quality). They are an extensively-edited version of reality: heightened, aestheticized, unreliable. The two are not yet integrated in any way other than that they are both genuine expressions of the same dualistic character. There’s room for improvement, and that’s a good thing. As a work of “outsider” art, the bar is pretty low, anyway.

Aesthetic Elements of Hypertext

- URL Schema

Cosma’s website has many pages, but the URLs are all quite schematic. To my mind, they clash with what we expect from websites nowadays. Incongruous URLs produce a certain effect, but I like Gwern’s approach of single-word URLs. Social media was not a concern for older Web pioneers. Now we must prioritize short, stable, “cool” URLs.

- Page Structure

One of the classic things that hypertext theorists love to talk about is linking. In many examples of early hypertextual works, made when monitors were much more primitive than today, pages were designed for a single viewport. In contrast to this, another version of the website is based on “long” pages, like a scroll. The idea is to create anchored sections that can be linked. Sub-sectioning can be challenging to pull off if the goal is “literary,” but there is a precedent for it in certain works of Contemporary literature. Linking makes the website a real work of art.

- Metadata

Like the URL, metadata is another element that is both aesthetic and technical, and which sits at the core of the website as a hypertext artwork. We want to think up metadata categories that can be used to represent the important aspects of a page. They will need to be standardized, somehow.

Bibliography

Peter Stormare’s representation of the doctor seems to access an archetypical image of the medicine-man as crusty drug-addict. Equal parts Peter Berling as the Doctor in Sátántangó, and Doctor Nick from The Simpsons.↩︎

“The precedent established by the end of the student struggles for pre-emption, technological surveillance and increasingly severe punitive response, was consolidated in the state’s handling of the riots. And the country was exceptionally well equipped for it too, having sleepwalked its way into being one of the most spied-upon nations in the world, with an estimated one CCTV camera for every 11–14 people. What followed was one of the biggest investigations in the history of the police force, Operation VERA, in which hundreds of specialists trawled through video footage in a race to identify the thousands of faces caught on camera.” Endnotes, “A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Crisis Era Struggles in Britain,” in Gender, Race, Class and Other Misfortunes, by Endnotes (Endnotes, 2013), https://endnotes.org.uk/articles/a-rising-tide-lifts-all-boats.↩︎

“The true objective of the reform movement, even in its most general formulations, was not so much to establish a new right to punish based on more equitable principles, as to set up a new ‘economy’ of the power to punish, to assure its better distribution, so that it should be neither too concentrated at certain privileged points, nor too divided between opposing authorities; so that it should be distributed in homogeneous circuits capable of operating everywhere, in a continuous way, down to the finest grain of the social body.” Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (1975; repr., New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 80.↩︎

“It may indeed be the highest secret of monarchical government and utterly essential to it, to keep men deceived, and to disguise the fear that sways them with the specious name of religion, so that they will fight for their servitude as if they were fighting for their own deliverance, and will not think it humiliating but supremely glorious to spill their blood and sacrifice their lives for the glorification of a single man. But in a free republic (respublica), on the other hand, nothing that can be devised or attempted will be less successful. For it is completely contrary to the common liberty to shackle the free judgment of the individual with prejudices or constraints of any kind. Alleged subversion for ostensibly religious reasons undoubtedly arises only because laws are enacted about doctrinal matters, and beliefs are subjected to prosecution and condemnation as if they were crimes, and those who support and subscribe to these condemned beliefs are sacrificed not for the common welfare but to the hatred and cruelty of their enemies. However, if the laws of the state ‘proscribed only wrongful deeds and left words free,’ such subversion could not be made to proclaim itself lawful, and intellectual disputes could not be turned into sedition.” Benedict de Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, ed. Jonathan Israel, trans. Michael Silverthorne and Jonathan Israel (1670; repr., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 6.↩︎

Advertisements play a significant role in the early history of mass media. They are a site of creative experimentation in graphic design; they also represent the naked greed of the bourgeoisie combined with the colonial ambitions of the state. They are horrific to behold.↩︎

“‘Here we have a man whose job it is to gather the day’s refuse in the capital. Everything that the big city has thrown away, everything it has lost, everything it has scorned, everything it has crushed underfoot he catalogues and collects. He collates the annals of intemperance, the capharnaum of waste. He sorts things out and selects judiciously: he collects like a miser like a miser guarding a treasure, refuse which will assume the shape of useful or gratifying objects between the jaws of the goddess of Industry.’ This description is one extended metaphor for the poetic method, as Baudelaire practiced it. Ragpicker and poet: both are concerned with refuse.” Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” in Selected Writings, by Walter Benjamin, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Harry Zohn, vol. 4 (1938; repr., Harvard University Press, 2006), 48.↩︎

“The precedent established by the end of the student struggles for pre-emption, technological surveillance and increasingly severe punitive response, was consolidated in the state’s handling of the riots. And the country was exceptionally well equipped for it too, having sleepwalked its way into being one of the most spied-upon nations in the world, with an estimated one CCTV camera for every 11–14 people. What followed was one of the biggest investigations in the history of the police force, Operation VERA, in which hundreds of specialists trawled through video footage in a race to identify the thousands of faces caught on camera.” Endnotes, “A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Crisis Era Struggles in Britain,” in Gender, Race, Class and Other Misfortunes, by Endnotes (Endnotes, 2013), https://endnotes.org.uk/articles/a-rising-tide-lifts-all-boats.↩︎

“It may indeed be the highest secret of monarchical government and utterly essential to it, to keep men deceived, and to disguise the fear that sways them with the specious name of religion, so that they will fight for their servitude as if they were fighting for their own deliverance, and will not think it humiliating but supremely glorious to spill their blood and sacrifice their lives for the glorification of a single man. But in a free republic (respublica), on the other hand, nothing that can be devised or attempted will be less successful. For it is completely contrary to the common liberty to shackle the free judgment of the individual with prejudices or constraints of any kind. Alleged subversion for ostensibly religious reasons undoubtedly arises only because laws are enacted about doctrinal matters, and beliefs are subjected to prosecution and condemnation as if they were crimes, and those who support and subscribe to these condemned beliefs are sacrificed not for the common welfare but to the hatred and cruelty of their enemies. However, if the laws of the state ‘proscribed only wrongful deeds and left words free,’ such subversion could not be made to proclaim itself lawful, and intellectual disputes could not be turned into sedition.” Benedict de Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, ed. Jonathan Israel, trans. Michael Silverthorne and Jonathan Israel (1670; repr., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 6.↩︎

“‘Here we have a man whose job it is to gather the day’s refuse in the capital. Everything that the big city has thrown away, everything it has lost, everything it has scorned, everything it has crushed underfoot he catalogues and collects. He collates the annals of intemperance, the capharnaum of waste. He sorts things out and selects judiciously: he collects like a miser like a miser guarding a treasure, refuse which will assume the shape of useful or gratifying objects between the jaws of the goddess of Industry.’ This description is one extended metaphor for the poetic method, as Baudelaire practiced it. Ragpicker and poet: both are concerned with refuse.” Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” in Selected Writings, by Walter Benjamin, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Harry Zohn, vol. 4 (1938; repr., Harvard University Press, 2006), 48.↩︎

Peter Stormare’s representation of the doctor seems to access an archetypical image of the medicine-man as crusty drug-addict. Equal parts Peter Berling as the Doctor in Sátántangó, and Doctor Nick from The Simpsons.↩︎

“The true objective of the reform movement, even in its most general formulations, was not so much to establish a new right to punish based on more equitable principles, as to set up a new ‘economy’ of the power to punish, to assure its better distribution, so that it should be neither too concentrated at certain privileged points, nor too divided between opposing authorities; so that it should be distributed in homogeneous circuits capable of operating everywhere, in a continuous way, down to the finest grain of the social body.” Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (1975; repr., New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 80.↩︎

Advertisements play a significant role in the early history of mass media. They are a site of creative experimentation in graphic design; they also represent the naked greed of the bourgeoisie combined with the colonial ambitions of the state. They are horrific to behold.↩︎