On 31 August 2023, Apocalypse Confidential published their third special of the year: DUST—JOHN FORD & THE ATOMIC FRONTIER. Included in the “non-fiction” section was an essay I wrote in response to the prompt. Light Enough to Burn a Hole in the Sun, a title I came up with early in the writing process and thought was good enough to not worry about changing, was written over roughly two weeks towards the end of August 2023. I spent around a week gestating in advance. I had only heard about the publication in the month or so prior. My memory is that I saw an old crush tweeting about them, but it’s possible that memory is a fabulation and I found them through conventional means (i.e. the platform’s timeline presented me with a stranger tweeting about them).

The second association that boosted my esteem for the publication was my friend C–, who stayed in my spare room during the final week of writing. He told me about Anna Krivolapova, who, by that time, the algorithm was definitely pushing on me. Her collection of short stories will be released by the publishing arm of Apocalypse Confidential this autumn. C– spoke highly of her, I think highly of him, and she thinks highly of APCON. Enough elements to make this publication stand out before having read them. I even went so far as to go through their website archives, and to read several pieces in order to get a sense of just what the project consists of. These initial associations, combined with the style of the call for submissions, combined with seeing Oppenheimer, fired my inspiration and led me to put a lot of energy into the essay I wrote for them. And I am quite proud of it. Finally I am working in the genre I want to. Finally, I can break free from the prison house of academic language; to paint a picture, while still developing the philosophical questions I am interested in.

One major element of the “literary” philosophical essay style, in my mind, is referencing things without necessarily providing citations. It would not have fit the epic voice I was going for to provide in-text citations. The purpose of this “commentary” is to provide a list of all the sources that I am conscious of having woven into the text. I am inspired by Kierkegaard, who, from the outset of his authorship, kept a series of large black notebooks where, in his own voice, not for publication but addressed to posterity, he provides yet another angle on his work. A running commentary and reflection on the published works.

The protagonist of the essay is Spirit, taken, of course, from Hegel and his Phenomenology. In the sense I am using it in the essay, it is intended to refer to the general movement of the totality of social history. “Spirit” is “history as it has developed so far.”

Spirit is thus self-supporting, absolute, real being. All previous shapes of consciousness are abstract forms of it. They result from Spirit analysing itself, distinguishing its moments, and dwelling for a while with each. This isolating of those moments presupposes Spirit itself and subsists therein; in other words, the isolation exists only in Spirit which is a concrete existence. … we may briefly recall this aspect of them in our own reflection: they were consciousness, self-consciousness, and Reason. … as unity of consciousness and self-consciousness, Spirit is consciousness that has Reason … when this Reason which Spirit has is intuited by Spirit as Reason that exists, or as Reason that is actual in Spirit and is its world, then Spirit exists in its truth; it is Spirit, the ethical essence that has an actual existence. — G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A. V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 264–65 / M440.

The central image of the essay is a drill boring through to the core of the earth. I am quite sure that I started writing before C– spoke about re-watching The Core, and this image was there from the outset. The association between “modernism” and “drilling, digging, excavating” is a common one that I could not give a single citation for. However, I realized only last week that I owe a greater debt to Glissant and his Poetics of Relation than I think I had previously realized.

Poetics of depth. Baudelaire explored the early realms of this form of poetics. The vertiginous extension, not out into the world but toward the abysses man carries within himself. Western man essentially, that is, who at that moment in time governed the evolution of modernity and provided its rhythm. Inner space is as infintely explorable as spaces of the earth. At the same time as he discovered the numerous varieties of the species man constituted, he felt that the alleged stability of knowledge led nowhere and that all he would ever know of himself was what he made others know. As a result, Baudelaire quashed romantic lyricism’s claim that the poet was the introspective master of his joys or sorrows; and that it was in his power to draw clear, plain lessons from this that would benefit everyone. This romantic beautitude was swept away by the stenches inseperable from Baudelairean carrion. — Ëdouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 24.

The next image is the idea of Azathoth, the lord of all the Outer Gods in Lovecraft’s Cthulhuverse, sitting at the centre of the universe. This was a significant adductive leap that came early in the process. It was my first clue that this was a serious essay. I’m not sure which Lovecraft story I read, or when—it may be that I only read the Wikipedia article some time ago—but some neuron fired, some crepuscular ray hit me, and I remembered that Azathoth was called the “Nuclear God.” As C– mentioned, this is quite simply an archaic use of the word “nuclear” to mean “at the centre of things,” but given that I was writing about Oppenheimer and the photo of the Trinity test, it felt like divine inspiration.

Never was a sane man more dangerously close to the arcana of basic entity—never was an organic brain nearer to utter annihilation in the chaos that transcends form and force and symmetry. I learned whence Cthulhu first came, and why half the great temporary stars of history had flared forth. I guessed—from hints which made even my informant pause timidly—the secret behind the Magellanic Clouds and globular nebulae, and the black truth veiled by the immemorial allegory of Tao. The nature of the Doels was plainly revealed, and I was told the essence (though not the source) of the Hounds of Tindalos. The legend of Yig, Father of Serpents, remained figurative no longer, and I started with loathing when told of the monstrous nuclear chaos beyond angled space which the Necronomicon had mercifully cloaked under the name of Azathoth. It was shocking to have the foulest nightmares of secret myth cleared up in concrete terms whose stark, morbid hatefulness exceeded the boldest hints of ancient and mediaeval mystics. Ineluctably I was led to believe that the first whisperers of these accursed tales must have had discourse with Akeley’s Outer Ones, and perhaps have visited outer cosmic realms as Akeley now proposed visiting them. — H. P. Lovecraft, “The Whisperer in Darkness,” Weird Tales 18, no. 01 (1931), full text.

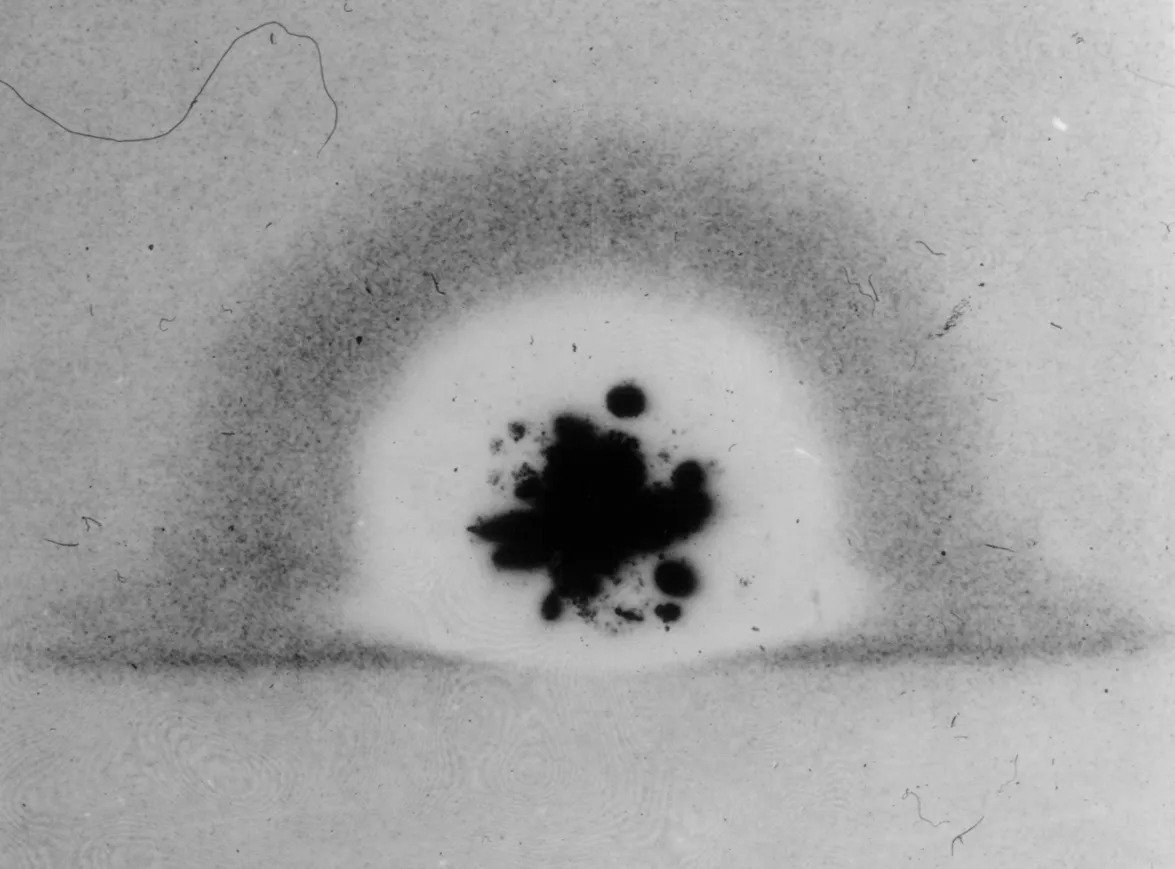

The next important ingredient is the photo of the Trinity test. This is also one of the few things that I started off knowing that I wanted to write about. Is the essay more a review of Oppenheimer, or more an analysis of this photo? You may notice that the colophon for this website is the “dark protozoic organism” that represents an “absence of medium.” This photo has been my banner image for years. I lifted it from an art history course I took in Winter 2018, led by Tal-Or Ben-Choreen. As I recall, she used it in the context of discussing what constitutes art: is this photo, taken for mechanical/scientific purposes, an artwork? She and I both stole it from The New Yorker, which remains the only source for the image online (as far as I can tell). I have not now and did not then read the article, only scrolled to steal the photo (in the pdf I submitted to APCON, I included a caption with citation details).

Past the halfway point, I added in yet another metaphor: the core of the earth is a “hollow world,” where cro-magnon man stalks pre-historic creatures. This is another fantasy image that I feel is so generic I don’t have a specific reference for it. My intuition from the outset is that ultimately comes from something by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Like the Lovecraft, another inheritance from my father. In doing research for this post, I discovered that ERB wrote a series about Pellucidar, which Tarzan visits in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

As a teenager, I used to write stories set at in the Hollow World about a pirate ornithopter, as big as a frigate, crewed by an assortment of intelligent animals. The main character was Hrothgrar, an “albino spirit bear,” whose name is an osmotic corruption of the Danish king Hrothgar. My best guess on how that word entered my consciousness is through Bulfinch’s Mythology. A combination of Redwall and Elric of Melniboné. The idea was that, spirit bears being all white, the albino version would be all black; and, spirit bears being the most rare type of bear, their culture would be highly refined: the wizards of bears. But my Hrothgrar, being an albino (the inverted form), would be huge and inarticulate, showing the influence of The Incredible Hulk, yet another childhood favourite.

“The layers of the earth weigh on Spirit’s head like a nightmare” is a spin on Marx’s famous line from a pamphlet published in 1852.

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionising themselves and things, in creating something entirely new, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, battle slogans and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language. Thus Luther donned the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789 to 1814 draped itself alternately as the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, in turn, 1789 and the revolutionary tradition of 1793 to 1795. In like manner the beginner who has learnt a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he has assimilated the spirit of the new language and can produce freely in it only when he moves in it without remembering the old and forgets in it his ancestral tongue. — Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in The Marx-Engels Reader, by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, ed. Robert C. Tucker, 2nd ed. (New York; London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 595. full text

The reference to “conquering reason” is an explicit reference to Glissant, who is himself referencing Deleuze & Guattari.

Summarizing what we know concerning the varieties of identity, we arrive at the following:

Root identity

- is founded in the distant past in a vision, a myth of the creation of the world;

- is sanctified by the hidden violence of a filiation that strictly follows from this founding episode;

- is ratified by a claim to legitimacy that allows a community to proclaim its entitlement to the possession of a land, which thus becomes a territory;

- is preserved by being projected onto other territories, making their conquest legitimate—and through the project of a discursive knowledge.

Root identity therefore rooted the thought of self and of territory and set in motion the thought of the other and of voyage.

Relation identity

- is linked not to a creation of the world but to the conscious and contradictory experience of contacts among cultures;

- is produced in the chaotic network of Relation and not in the hidden violence of filiation;

- does not devise any legitimacy as its guarantee of entitlement, but circulates, newly extended;

- does not think of a land as a territory from which to project toward other territories but as a place where one gives-on-and-with rather than grasps

Relation identity exults the thought of errantry and of totality. — Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 143–44.

In the sections where I discuss cinema more explicitly, I reference the “transcendental perspective of the camera.” This concept is taken from Christian Metz, who writes that the most basic pleasure of cinema comes not through identification with characters or narrative—but from identification with the perspective of the camera itself.

In other words, the spectator identifies with himself, with himself as a pure act of perception (as wakefulness, alertness): as the condition of possibility of the perceived and hence as a kind of transcendental subject, which comes before every there is. — Christian Metz, “Identification, Mirror,” in Psychoanalysis and Cinema: The Imaginary Signifier, by Christian Metz, trans. Celia Britton et al. (London: Macmillan, 1982), 49.

Around this same section, I refer to Denis Villeneuve and Christopher Nolan as the two fathers of the “house Netflix style.” I didn’t come up with this: I think it was my professor Luca Caminati. I think it is 100% true.

The idea of climbing up the sides of the ziggurat to become one with the sun is an image that keeps returning to me. It’s in another piece of writing that I am currently working on. It references Aztec cultures more so than to the Old Kingdoms of Egypt. It’s almost certainly an image taken from some racist text, but hopefully its origin in antiquity is neutral enough to cancel out any cancellable offense. I will not be surrendering the ziggurat, no matter how much the woke mob might clamour of my blood.

The idea that modern art is characterized by an “absolutely subjective, arbitrary [aesthetic] vocabulary” is an idea I took from the book The Crisis of Ugliness, a book by the Soviet art critic Mikhail Lifshitz.

Cubism is characterized by its incursions into the field of the theory of knowledge.

It sees the greatest danger in the visual perception of the real world. If the world is bad, it is vision that is to blame for reproducing it to us again and again. In its assumption that visual perception gives us images of the real world, the old painting attempted to convey these images with the greatest possible fidelity and fullness. The modernist schools reach for exactly the opposite result: all their discoveries are a ‘sum of destructions’ aimed against the perception of the ordinary person. Things-in-themselves do not exist or are unknowable to us; truth consists in the artist’s subjective experience. Properly speaking, this false axiom was already found by the predecessors of the Cubists, who now only had to make the next step: from the simple negation of ‘naïve realism’ to the total rejection of vision as the basis of painting. — Mikhail Lifshitz, The Crisis of Ugliness: From Cubism to Pop-Art, trans. David Riff, vol. 158, Historical Materialism (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 84.

The “predecessors” of cubism here are all the various styles of modern art that had already flourished throughout Europe by the turn of the 20th century. Although this essay is a study of cubism, the book is generally concerned with the “crisis of ugliness,” i.e. the loss of mimesis and the turn towards conceptual art in modern culture generally. What I find to be so special about this book, aside from Lifshitz’s extremely erudite analysis and excoriating remarks on art critics and theorists, is its outsider perspective. The book comes not only from another time, but from a world that no longer exists (the USSR).

“A new religion of art.” At the end of the Phenomenology, Hegel describes how the stage beyond the current can only theoretically be realized in the form of religion, the path to absolute knowing. Religion in the sense we know it, as in worship of the divine; or a religion of art. Both seem to be valid.

In the condition of right or law, then, the ethical world and the religion of that world are submerged and lost in the comic consciousness, and the Unhappy Consciousness is the knowledge of this total loss. It has lost both the worth it attached to its immediate personality and the worth attached to its personality as mediated, as thought. Trust in the eternal laws of the gods has vanished, and the Oracles, which pronounced on particular questions, are dumb. The statues are now only stones from which the living soul has flown, just as the hymns are words from which belief has gone. The tables of the gods provide no spiritual food and drink, and in his games and festivals man no longer recovers the joyful consciousness of his unity with the divine. The works of the Muse now lack the power of the Spirit, for the Spirit has gained its certainty of itself from the crushing of gods and men. They have become what they are for us now—beautiful fruit already picked from the tree, which a friendly Fate has offered us, as a girl might set the fruit before us. It cannot give us the actual life in which they existed, not the tree that bore them, not the earth and the elements which constituted their substance, not the climate which gave them their peculiar character, nor the cycle of the changing seasons that governed the process of their growth. So Fate does not restore their world to us along with the works of antique Art, it gives not the spring and summer of the ethical life in which they blossomed and ripened, but only the veiled recollection of that actual world. Our active enjoyment of them is therefore not an act of divine worship through which our consciousness might come to its perfect truth and fulfilment; it is an external activity—the wiping-off of some drops of rain or specks of dust from these fruits, so to speak—one which erects an intricate scaffolding of the dead elements of their outward existence—the language, the historical circumstances, etc. in place of the inner elements of the ethical life which environed, created, and inspired them. And all this we do, not in order to enter into their very life but only to possess an idea of them in our imagination. But, just as the girl who offers us the plucked fruits is more than the Nature which directly provides them—the Nature diversified into their conditions and elements, the tree, air, light, and so on—because she sums all this up in a higher mode, in the gleam of her self-conscious eye and in the gesture with which she offers them, so, too, the Spirit of the Fate that presents us with those works of art is more than the ethical life and the actual world of that nation, for it is the inwardizing in us of the Spirit which in them was still [only] outwardly manifested; it is the Spirit of the tragic Fate which gathers all those individual gods and attributes of the [divine] substance into one pantheon, into the Spirit that is itself conscious of itself as Spirit. — Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, 455–56 / M753.