“An incident occurred,” the facilitator told us in a lecture before our class visit to Concordia University’s Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery. We were being prepared to go see Thinking Again and Supposing. Trajectory of an Exhibition, a joint show by Concordia professors and artists Sarah Greig and Therese Mastroiacovo. Described as an act of vandalism, the “incident” had been repeated to the class in tragic tones by various representatives of the Montréal artworld. As in our classroom, no natural light reaches this deep inside the institution.

Nothing had been intentionally slashed, only negligently reclined-upon. The first room of the gallery consists of two long pieces: a sawhorse table set up with thick, lead-grey shingles of silver gelatin paper; and a low rectangular structure covered with a fine treatment of graphite. Both works extend at gentle orthogonal angles the length of the long room. ON NOW? CONTEMPLA— (2022) perfectly resembles a bench, outlines of typography the only indication that it has been treated for aesthetic effect—but these details are ten or more paces away, the length of which is now interrupted by the white outline of a figure reclining. The environment of the gallery is so stark that it seems unsurprising the public would have a difficult time adjusting. The “incident” we had been warned about ultimately works to the benefit of the show, whose theme of institutional critique is given hard stakes by the ire of public indifference.

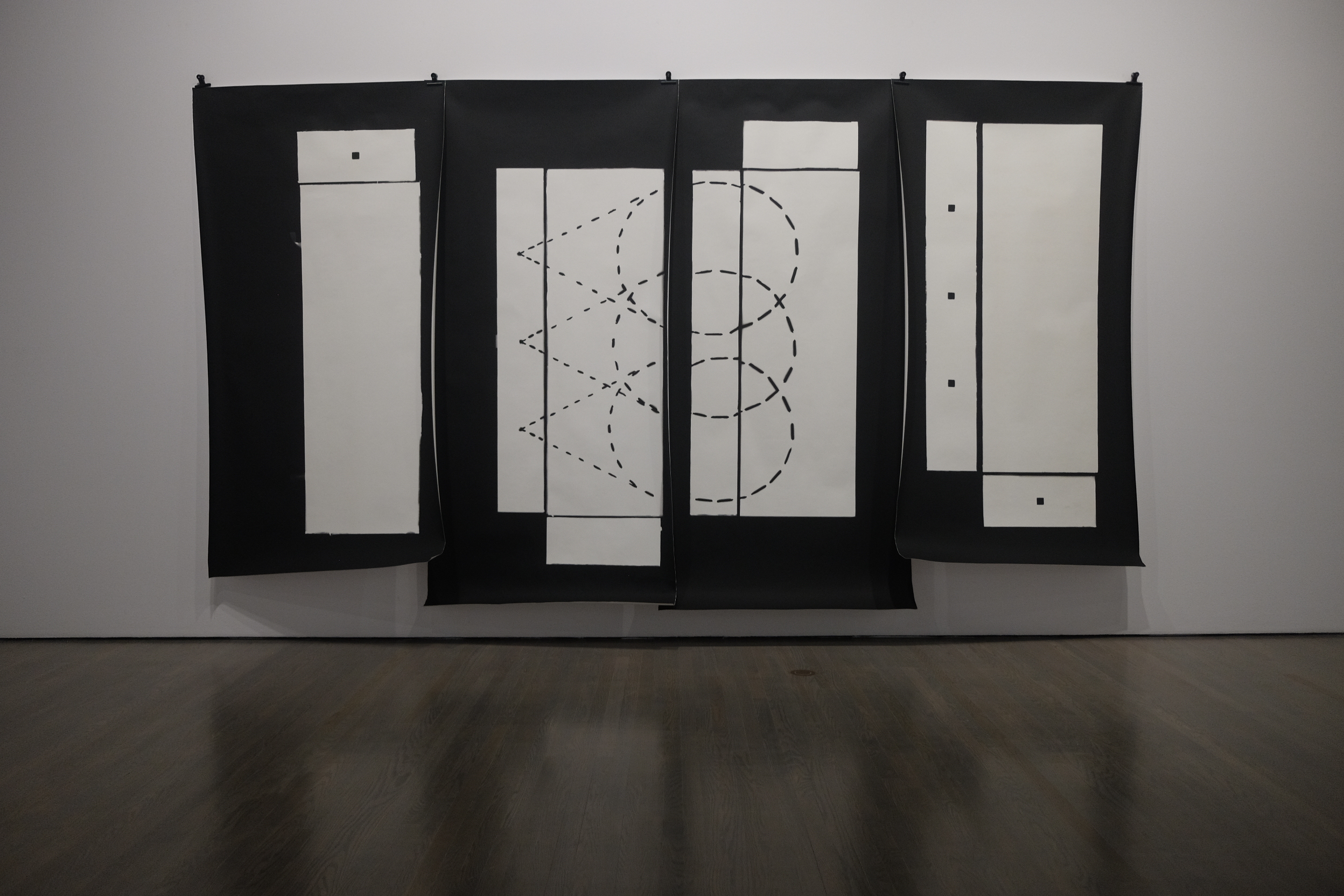

The show is a joint effort between the two artists alongside curator Michèle Thériault, all of whom have a history of collaboration. The strength of this working relationship shows in the careful choreography of the gallery’s layout, adroitly navigating the viewer through an aesthetically consistent conceptual exploration of media. Large-scale photo prints hang in the next room, curling rough-treatments pushing against the flat wall, fastened by oversized bulldog clips. Long View Study, one of the series by Greig, shows a dotted-line cone drawn against contrasting black and white boxes. Geometric abstraction and the aesthetics of draughtsmanship repeat throughout the gallery, even in works that use sculpture to confront us with the photographic.

On another one of these slabs of rippling gelatin paper, a pin-hole photograph makes out the same gallery we are walking through. The institution is incorporated into the visual repertoire of the show. It becomes blatant in the last room of the gallery, a small, confined area with its own feel of a distinct environment. It’s not until this room that the show’s political content becomes unavoidable. The large photo-works are cold, minimal, but highly aestheticized in the richness of their texture. The sculptural element of the show is already enough to remind us of where we are. In the last room, a series of posters by Mastroiacovo make a series of puns that lets us know unmistakeably what the themes of the show are. In contemporary art, it is no longer sufficient to make the institution the object of its own gaze. These works acknowledge the impossible relationship between culture and institutional power. Post-modernism and ironic detachment have been status quo. High, popular, and low culture are represented by meticulous pencil strokes, effaced to show their division remains a problem for the artists.

This leads us back to the first room of the gallery, where “the incident” occurred. The public, a category which represents the mass and is hence associated with “low” culture, did not respond well to the show. This show is a very consistent aesthetic unity that articulates a recognizable structure, even in what might seem like a restrictive space. And yet, it is intensely alienating on the surface, visually minimal and highly conceptual. Both trademarks of the contemporary “high art” style. The show is deeply embedded within the institution of Montréal’s artworld, but it is concerned about that institution’s status with respect to the public—and the public responded by laying over a painstakingly-applied dusting of graphite, posing for a photo and destroying the work.

What could be a more perfect validation of the show’s attempt to break through institutional sanctity? The conceptualist aesthetic still has the power to provoke audiences into responses as sacrilegious as violating the holy sanctity of an artwork. The negligence of this incident does not indicate indifference, but rather a show whose force was powerful enough to bridge the rift between the high culture of the Montréal artworld, and the indifferent masses.